After decades of debate – always vigorous, often heated, sometimes acrimonious – agreement was finally reached at COP27 last year to establish a loss and damage fund. The fund’s remit was simple – to offer financial help to those countries most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Developed countries, those most responsible for rising temperatures, will help developing countries, those least responsible.

Work began almost immediately on hammering out the key details of the fund and at a meeting earlier this month, a draft proposal was agreed. The fund will sit in the World Bank and contributions will be voluntary. The proposal will be keenly discussed at COP28 later this month.

Extreme damage

Africa is where the need for assistance is greatest, for despite being responsible for just 3% of global CO2 emissions, it is the most vulnerable continent to the impacts of climate change. Last year alone, climate-related events caused more than $8.5bn in damages, according to the World Meteorological Organization. With emissions and temperatures continuing to rise, the impacts will only get worse. Indeed between 2020 and 2030, the costs are expected to be between $290bn and $440bn, according to the African Development Bank. It says the continent is already losing between 5% and 15% of its per capita GDP. This could rise to 34%, says Christian Aid.

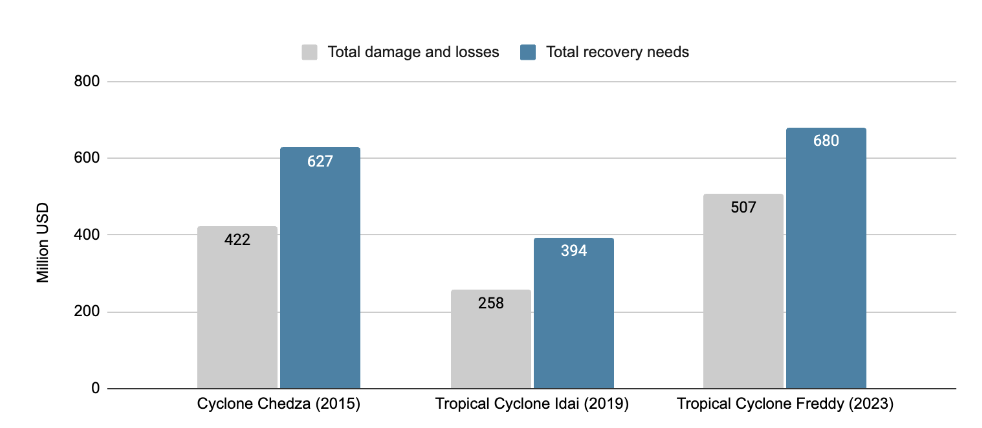

Malawi is a country that’s been hit particularly hard. It is one of the poorest countries in the world, with more than half its population living below the national poverty line. The country’s economy is heavily reliant on agriculture, which employs 80% of the population, and so is incredibly vulnerable to extreme weather, particularly changes in rainfall. For example, early this year during Tropical Cyclone Freddy, the country suffered six months of rain in just six days, displacing 659,000 people, damaging 260,000 houses and road networks, and destroying vast tracts of crops. The cyclone is estimated to have caused more than $500m of damage, with the cost of recovery and reconstruction at $680m, almost 6% of the country’s GDP.

These kinds of events are becoming more common. Cyclone Freddy came hot on the heels of two other major cyclone events in 2022, and was the fifth since 2015. The country had little time to recover from one before the next hit, which collectively caused extraordinary economic damage and instability. Indeed the impacts of climate change could cut annual GDP by up to 20% by 2040, according to a World Bank study.

Costs of Malawi cyclones

Source: Government of Malawi, 2023.

Expensive debt

Malawi and other African countries’ ability to withstand such economic devastation is severely hampered by their levels of debt. To respond to and recover from natural disasters they need to borrow money, yet many are already servicing high levels of debt. Borrowing money is, therefore, extremely expensive – typically three times higher than for a developed country (10.5% vs 3.5% interest) – as lenders factor in current debt levels and the risk of future climate events.

The cost of servicing these debts means many countries have to cut back on essential public services and building resilience to climate change.

Fund-amental issues

Addressing these fundamental issues will be high on the agenda at COP28. There are a number of key points to thrash out. The current proposal to house the loss and damage fund in the World Bank is not popular among developing countries, which would prefer the fund to be an entirely new mechanism. They also want the fund to be demand driven and cover all types of economic and non-economic losses. A number of developing countries, including the US, have suggested a more limited scope covering just non-economic losses, such as heritage. There are also differing views on who should pay into the fund. The proposal suggests richer countries that have emitted the most greenhouse gases historically should pay, but there is disagreement over whether other, more recent polluters such as China and India, as well as oil-producing states, should contribute. Finally, there are differing views on who should receive the funds. The wording agreed at COP27 referred to those countries that are “particularly vulnerable”, but some countries would prefer that only specific nations, such the Small Island Developing States, benefit.

The scale of funding will be key. Estimates of the total cost of loss and damage globally by 2050 range from $500bn to $4tn, depending on the level of warming. In 2020, developed countries contributed $83bn in climate finance, just a quarter of which went to Africa. Developing nations are proposing a minimum of $100bn should be raised by 2030. So far, just $294m has been pledged, almost two-thirds of which is from Germany.

Precedents do not bode well. In 2009, developed nations pledged $100bn annually in climate finance. The latest figures for 2020 show they were still falling well short. African nations, together with developing countries around the world, will be pushing hard at COP to ensure the same doesn’t happen again.