In this deep dive:

- What are the limitations of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)?

- What exactly are Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)?

- How has the IMF responded to today’s global crises through SDR allocation?

- What’s SDR rechanneling, and how could it work?

What are the limitations of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was established alongside the World Bank in the aftermath of World War II to rebuild the international economic system. While both organizations have played a crucial role in stabilizing the global economy and reducing poverty in developing countries, their governance structure has come under scrutiny in recent years.

Critics argue that the current system favours advanced economies and grants the United States significant veto power over key decisions. IMF voting shares are based principally on economies’ size and “market openness”. This has led to imbalanced voting power, with emerging markets and climate-vulnerable countries underrepresented in decision-making processes.

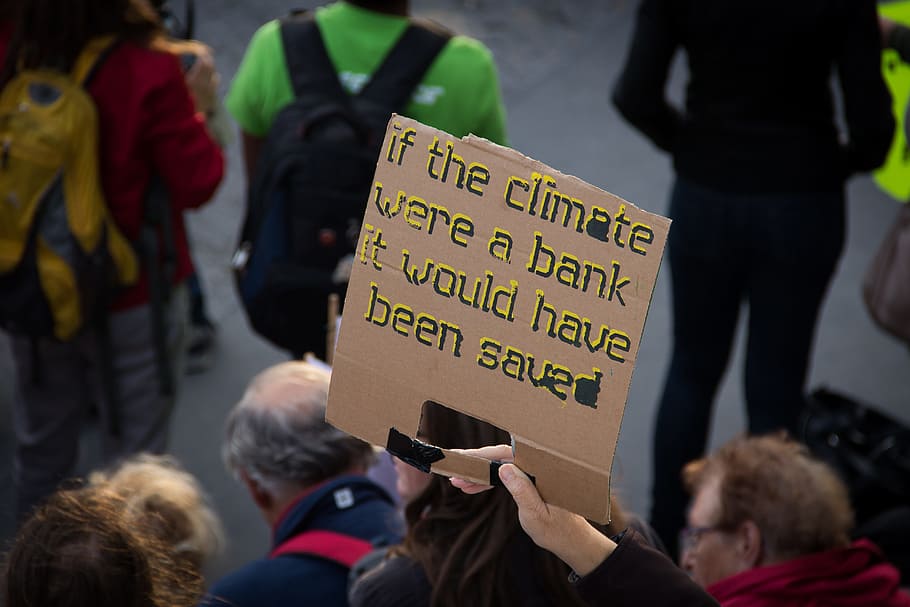

Now, as the world faces an urgent challenge in the form of climate change, calls for reform are growing louder. The IMF’s mandate to oversee monetary system stability and the World Bank’s mission to reduce poverty remains crucial, but the need for fair and effective governance has never been greater.

In September 2022, Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados, set out a bold vision for financial reform called the Bridgetown Agenda, including practical solutions to address the underlying inequalities present in international financial institutions like the distribution of SDRs.

What exactly are Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)?

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) were originally established by the IMF as a means of supplementing the reserves of member countries. These reserves, which can be exchanged for hard currency such as dollars, pounds or euros, provide a country with liquidity. SDRs themselves cannot be used directly to purchase goods or services, but they serve as a medium of exchange that can be used to obtain the hard currency needed to import necessary resources or service outstanding debts.

For example, if a country is facing a shortage of foreign resources required to import goods, it can use its SDRs to exchange for another member’s reserves. This allows the country to obtain the hard currency necessary to purchase those resources and keep its economy running smoothly. Additionally, SDRs can be used as payments to other SDRs holders, such as when servicing debts.

While SDRs are not a currency in the traditional sense, they play a vital role in facilitating international trade and commerce by providing a means of exchange that can be used to obtain the hard currency necessary to keep economies functioning smoothly. As such, they are an important tool for ensuring global economic stability and should be carefully managed and utilised.

How has the IMF responded to today’s global crises through SDR allocation?

The COVID-19 pandemic took a significant toll on the global economy, resulting in an estimated loss of around US$4 trillion in 2020. In response to the crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank boosted their support in 2020. The global financial community also rallied behind the idea of an allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) as a means of providing all central banks with an immediate and unconditional boost to their foreign currency reserves. This would have enabled governments to manage their internal and external finances more effectively.

While some experts argued that a US$3 trillion SDR allocation was required to tackle the financing challenges facing emerging markets worldwide, the proposal was stalled due to a lack of support from the Trump administration. However, with the arrival of the Biden administration, the allocation was approved.

In 2021, equivalent to about US$650 billion of SDRs were distributed to help countries struggling with the impact of COVID-19. However, the allocation of SDRs followed the IMF’s historical quota system, which primarily benefited developed countries and China, which already possessed substantial reserves. Unfortunately, the distribution of SDRs did not consider the economic needs of each country.

Instead, the IMF distributed funds based on economic size and existing reserves, resulting in the world’s wealthiest nations receiving the bulk of the US$650 billion. Meanwhile, African countries received only 5% of the total, equating to a mere US$33 billion in SDRs. This uneven distribution highlighted the current imbalance within the global economy, where the poorest nations were left to struggle while the richest continued to prosper.

What’s SDR rechanneling, and how could it work?

The uneven distribution of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) in 2021 sparked discussions about redistributing the reserves to address global inequality and bridge financial gaps between nations. As a result, G20 countries made a collective promise to rechannel a combined US$100 billion of their SDRs to lower-income countries in need of funds to stabilize their economies, reduce their debt burdens, and invest in climate solutions.

Efforts to rechannel SDRs by developed countries are being monitored by The One Campaign initiative. As of February 2023, a total of US$60 billion worth of SDRs had been pledged (excluding US$21 billion from the USA, which Congress has not yet authorized).

However, while developed nations have committed to recycling SDRs for countries in need, the process of transferring the reserves is not a simple one.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has announced two channels for recycling Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) worth a total of USD 65 billion. The Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGT) and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) will be utilized for this purpose. While the IMF is yet to provide further details on the PGRT, it has committed to lending US$2.5 billion of SDRs to five countries – Costa Rica, Barbados, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Jamaica – through the RST.

However, in order to fulfil the G20’s commitment of US$100 billion, additional options for recycling SDRs need to be explored. The IMF has approved five new institutions to hold SDRs, including the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, the Caribbean Development Bank and the Latin American Development Bank (CAF).

As part of the Bridgetown Agenda, a Global Climate Mitigation Trust has been proposed, backed by US$100 billion in SDRs. This trust would fund projects that have already been proven to be effective in mitigating climate change, while also meeting the highest environmental, social and governance standards. Investment managers would select projects based on their potential contribution to reducing global warming.