Usually a large presence at COPs, this year oil and gas companies have been deliberately sidelined, leaving them feeling a little miffed. Quite why large oil companies, whose products directly contribute to the problem and who’ve shown a remarkable unwillingness to address it, feel they should have a big role to play at a climate negotiation is a question for them.

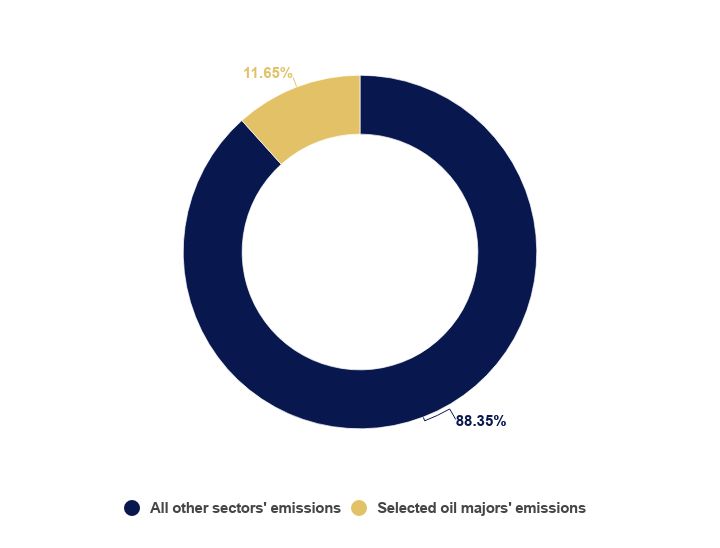

The oil and gas sector accounts for about 42% of total global emissions. In 2020, just six of the largest independent oil and gas companies – Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEneriges, BP, Equinor, Eni and Repsol – alone contributed more than 11% of emissions (see Figure 1).

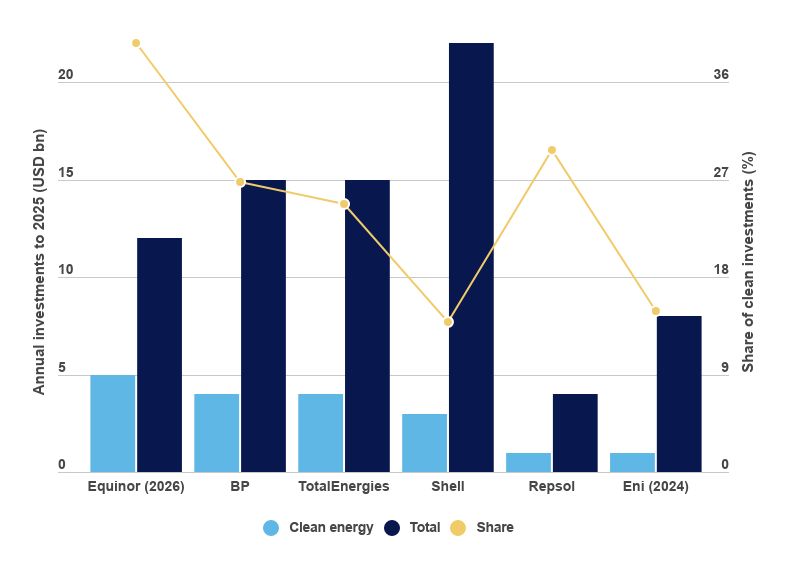

They regularly point to their own decarbonisation targets and it’s true that a number of the oil majors have issued net-zero targets. They are also investing in renewables. By 2030, TotalEnergies aims to build out 100 GW of renewables, while BP targets 50 GW. The share of annual investment has also risen from a paltry 5% to levels closer to 20% (see Figure 2). Some state that this share will rise to closer to 50% by the end of the decade.

But is this just window dressing? Let’s peer beneath the surface and see what these ‘commitments’ really entail.

Old habits die hard

The fact remains that the majors spend many times more money on developing new oil and gas than they do on renewables. In fact most appear fixated on natural gas – as the peak of oil demand beckons, they seem to think that shifting to gas will help secure high returns for decades to come. TotalEnergies aims to increase its liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacity by 30% by 2030, Eni is targeting a 90% gas-weighted portfolio by 2050 and Shell will spend USD 4 billion annually on its gas business over the next few years. This appears unwise – as the pace of global decarbonisation quickens, gas assets will soon run the risk of being stranded.

The majors also continue to rely on contentious decarbonisation methods. For one, they are involved in several large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects. Current CCS technology does not capture sufficient amounts of CO2 to be considered carbon neutral. And that’s before we consider the difficulty in building out the technology. So far, projects have struggled to scale and operate effectively.

Offsetting, not decarbonising

Net-zero strategies are also particularly weak. For a start, most oil majors have only set intensity-based reduction targets – cutting the amount of CO2 they emit per barrel of oil they produce – which don’t guarantee emissions cuts (and could in theory allow for emissions to rise). Ultimately, to rein in climate change, emission cuts need to be absolute, and only one oil major seems to have an effective plan to introduce them: Eni.

There’s value in going green: A case study of Ørsted

Though by no means a perfect comparison, Ørsted illustrates the value that decarbonising can create. As Danish Oil and Natural Gas (DONG), the company made a drastic strategic shift away from fossil fuels and towards offshore wind. Since listing in 2016, its stock price has risen by 252%.

Net-zero strategies are also based heavily on offsets. As things currently stand, BP, Eni, TotalEnergies and Shell would require an area twice the size of the UK to meet the tree-planting targets they have set for themselves, according to an Oxfam report. Clearly this is not a sustainable and scalable solution. In fact there are numerous issues with relying on offsets to achieve net-zero targets.

The oil majors, then, must do far more to show they are serious about decarbonising. Perhaps then they may be invited back to COP.