Wind generation in Africa is set to increase dramatically, according to a new report from the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC).

It identified 140 planned projects totalling 86 GW, almost ten times current installed capacity. While South Africa and Egypt will continue to dominate the sector, a number of countries will be building wind farms for the first time, including Angola, Malawi, Sudan, Uganda and Zambia.

The report highlights a number of benefits from building out wind capacity, including economic opportunities, both from selling power and creating jobs, grid stabilisation and diversification of supply.

Huge potential

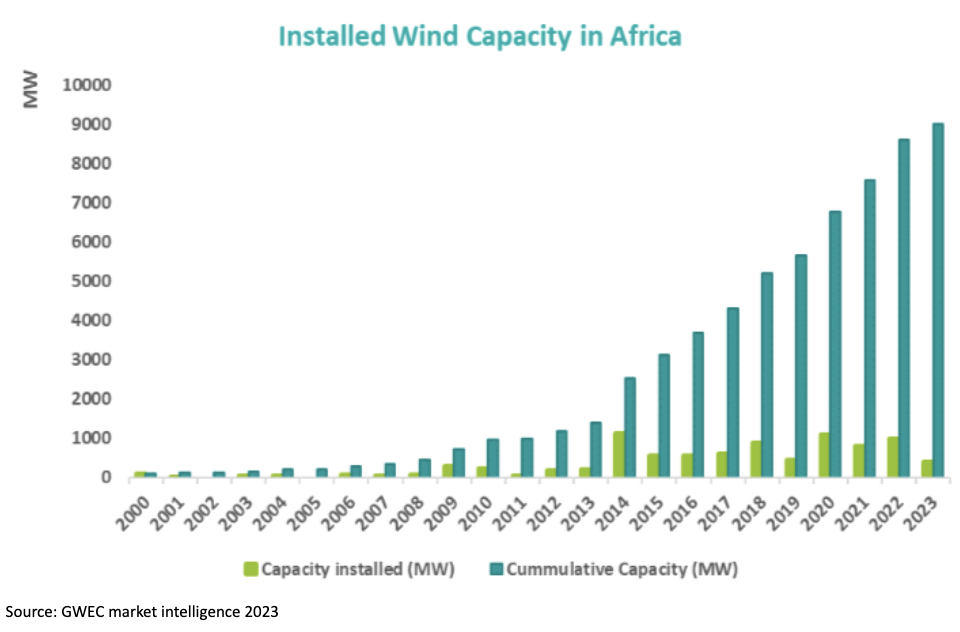

Wind capacity in Africa has risen steadily over the past 20 years, with four of the past five years seeing almost 1 GW of additional capacity. The traditional strongholds of South Africa, Egypt and Morocco have been joined by Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania, among others, as every region bar Central Africa capitalises on the benefits of wind power.

The report identifies 9 GW of installed capacity, which includes projects under construction and scheduled to be commissioned this year. This is enough to power 19 million homes and save 24.4m tonnes of CO2.

This is just the beginning, however. A further 86 GW of capacity is already planned across 140 projects, including in Central Africa for the first time, with 700 MW across 13 sites in Angola. Other countries set to build wind farms for the first time include Chad, Mali, Ghana, Niger and Madagascar.

Egypt has the most ambitious plans, thanks in part to its established local manufacturing industry, with around 30 GW in the pipeline. This includes a 10 GW farm in the Gulf of Suez that will be one of the biggest in the world. South Africa is not far behind, with plans for around 27 GW. Next comes Morocco with around 11 GW and Algeria with 5 GW.

These numbers are dwarfed by the potential for wind power on the continent. According to the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), the “stunning” technical potential capacity across Africa is 33,642 GW, which would be enough to meet energy demand 250 times over. The countries with the most technical potential are Algeria, Libya, Sudan, Mauritania and Chad.

Installed vs potential capacity by region

| Region | Installed capacity | Potential capacity |

| North Africa | 4.2 GW | 19,000 GW |

| West Africa | 296 MW | 9,100 GW |

| Central Africa | 0 GW | 2,700 GW |

| East Africa | 1 MW | 2,100 GW |

| Southern Africa | 3.7 GW | 891 GW |

Source: GWEC market intelligence 2023

Economic benefits

There are a number of factors driving wind energy growth in Africa, many of which are common to countries across the world. There is currently huge unmet demand for power across the continent, highlighted by the fact that half the population of Sub Saharan Africa does not have access to electricity, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). In Chad, the Central Africa Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the figure is less than 10%. Wind offers an opportunity to increase supply of energy that is clean and affordable – on average across the continent it will be cheaper than gas by 2030, according to the IEA.

Earlier adopters in particular will also be able to take advantage of regional power markets by selling excess power to neighbouring countries. This can be when winds are strong and/or if generating capacity is complemented by energy storage technologies. This will be enabled by the Africa Single Electricity Market, launched by the African Union in 2021, which is looking to interconnect 55 African countries with a view to trading electricity.

The rollout of wind energy also provides great opportunities for employment. Across 3 GW of wind projects in Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, Senegal, Egypt and Morocco, the GWEC report identified 12,400 direct jobs created during and after construction. For example, the 310 MW project in Lake Turkana, Kenya, employed 2,500 people during construction and employs 329 for operations. Given there are 86 GW of planned wind projects across Africa, these numbers suggest hundreds of thousands of people could be employed in the construction of wind farms.

The report also outlines the benefits of supply diversification that wind energy brings. A number of countries in Africa rely on hydropower plants, which are becoming increasingly hit by drought due to climate change. Equally, many rely on imported fossil fuels, the cost of which has increased significantly in the last two years. Securing a more reliable, domestic supply of energy in the form of renewables overcomes both these problems. Egypt, for example, which currently uses fossil fuels to generate 80% of its electricity, wants renewables to account for more than 40% of its power mix by 2030.

The rollout of electric trains and buses across many countries, again to reduce demand for imported fossil fuels as well as reduce emissions, is also driving demand for wind power, the report says. A number of countries, including Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania, are also actively electrifying more personal modes of transport, such as two and three-wheelers.

Finally, industrial companies are installing wind farms to supply their power needs directly in order to reduce both their costs and their carbon footprints. This is particularly the case in Morocco’s cement and fertiliser industries, and in South Africa.