More than 100,000 pieces of scientific literature boiled down into 36 pages – the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a significant piece of work, and the result of a major global collaboration. Some 780 scientists – 41 per cent of whom come from developing nations – volunteered their expertise to work on it. Governments are also involved, meeting in Switzerland over seven days to agree the wording, line by line.

Known as the Synthesis Report, the document summarises the findings of a series of assessments undertaken by the panel since 2014. These cover climate science, mitigation and adaptation, as well as the contents of special reports on land-use change, frozen lands and the impacts of a 1.5°C rise in temperatures.

It has been badged as the IPCC’s “final warning” since there is unlikely to be another IPCC report before 2030, by which time the world will have exceeded the carbon budget to keep temperature rise within the 1.5°C agreed by governments in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The main purpose of the synthesis report is to bring together the findings of the IPCC’s latest cycle in one place, to aid policymakers and governments. As such, it does not contain new science. However, it does spell out “road signs” on the way to 2050, the deadline for the world to reach net zero emissions in order to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C – by 2030, the world needs to reduce emissions from 2019 levels by 48%, by 65% by 2035, and by 80% by 2040.

The report reiterates that humans are unequivocally causing climate change with global surface temperature reaching 1.1°C above industrial temperatures in 2011–2020. Fossil fuel use is overwhelmingly to blame – in 2019, around 79% of global GHG emissions came from energy, industry, transport and buildings, and 22% came from agriculture, forestry and other land use. CO2 emissions reductions from efficiency measures are dwarfed by rising emissions in multiple sectors.

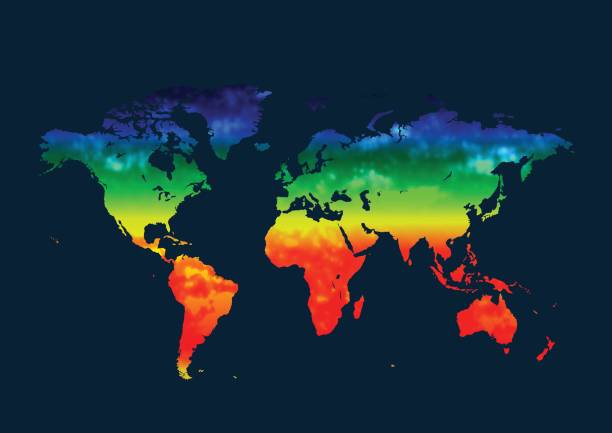

Every region of the world is already affected by extreme weather, the report states. However, vulnerable communities that have contributed the least to climate change are being disproportionately affected – some 3.3-3.6 billion people live in areas that are highly vulnerable to climate change, and these people were 15 times more likely to die from floods, droughts and storms between 2010-2020 than those living with very low vulnerability.

Climate change has reduced food and water security, and extreme heat is leading to increased deaths and disease, as well as mental health challenges from extreme events and loss of livelihoods. Ecosystems and biodiversity are also being affected, the scientists say, pointing to mass mortalities of species both on land and in the ocean. Some ecosystems are getting close to a point of no return.

The IPCC acknowledges that mitigation efforts have expanded considerably since its last round of assessments. Renewable energy, urban green infrastructure, energy efficiency, improved management of forests, crops and grassland, and reduced food waste and loss, are all technically viable, and are becoming increasingly cost effective and generally supported by the public, it states.

However, policies implemented by the end of 2020 are projected to result in higher global GHG emissions in 2030 than is implied by national climate plans. If this is not reversed, the world is on track for global warming of 3.2°C by 2100, the report states.

Finance gaps are still a major issue, with three to six times current levels needed. Despite there being sufficient global capital to close investment gaps in climate solutions, barriers still exist in redirecting capital to climate action, particularly for developing countries, the IPCC states. Levels of finance for both mitigation and adaptation are still heavily outweighed by finance flowing to fossil fuels.

Keeping warming within 1.5°C represents greenhouse gas emissions reductions that are “rapid, deep, and, in most cases, immediate” in all sectors, this decade, it says. Despite the size of the challenge, the scientists say the goal is still achievable, just. But even under the most positive emissions reduction scenario, scientists believe warming will breach 1.5°C before 2040.

If temperatures rise beyond this, they could theoretically be bought back down again via Carbon Dioxide Removal, such as tree planting or carbon capture of emissions at power plants. However, damage to ecosystems caused by the increased warming – such as permafrost thaw and wildfires – would make this challenging, they warn. Some ecosystems, particularly in mountains, polar or coastal areas, would be irreversible, the report adds.

Existing impacts of climate change mean that action to adapt to extreme weather and higher temperatures is urgent, the IPCC says. Awareness and policies have grown, but still fall short of what is needed. There are significant funding gaps, with the vast majority of climate finance directed at mitigation rather than adaptation.

Some communities and ecosystems on the climate frontlines are already reaching the limits of adaptation, the IPCC warns. Adaptation options that are feasible and effective today will become much less so as global warming increases, and permanent impacts of climate change will become difficult to avoid, it states.

Ultimately, the IPCC points out, societies stand to gain many positives from ambitious mitigation and adaptation actions. For example, many measures to cut burning of fossil fuels will improve human health due to reductions in air pollution, and shifts to healthier diets. Many adaptation measures can boost food security and biodiversity.

Responses to the IPCC’s report echoed its message of urgency. The report clearly implies that coal, oil and gas must be phased out immediately, according to Olivier Bois von Kursk, policy analyst at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, while Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, stressed the importance of huge investment in clean energy to both the climate fight, and to boost energy security.

Laura Clarke, chief executive officer of environmental law firm ClientEarth warned leaders that continued lack of action on climate was increasingly likely to lead to litigation.

The IPCC report will be a key input to the Global Stocktake, a two-year assessment of the progress towards meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. It is due to be concluded at COP28 in Dubai in December, and will inform the development of new and more ambitious climate plans by governments in time for the next round of submissions in 2024-2025.

Simon Stiell, UN climate change executive secretary, said: “If we are to halve emissions by the end of the decade, we need to get specific now. This year’s Global Stocktake is a moment for countries to agree on the concrete milestones that will take us to our 2030 targets.”

There must be detailed steps for all sectors and themes, including climate adaptation, loss and damage, finance, technology and capacity building, he said. “COP28 can be the moment where we start to course correct to collectively meet the Paris goals.”