Carbon capture and storage (CCS) refers to a range of technologies that aim to capture carbon dioxide at point of source (typically a power plant or industrial facility), then transport and permanently store the gas underground.

Navigating CCS at COP28

What is CCS and why will it be a crucial topic at COP?

The process of capturing CO2 before it is emitted into the atmosphere is known as ‘abating’ emissions – although the term itself is yet to be properly defined.

Major oil and gas producers see abating emissions – via the use of CCS – as a key element in reaching net zero goals. After all, the alternative – which is phasing out fossil fuel production – is incompatible with their business model.

Given carbon emissions need to halve by 2030 to keep the world on track for a 1.5°C rise in temperature, the timescale available for enacting policies to deliver such a pathway is extremely tight.

So CCS is expected to be a key battleground at COP28, with major oil and gas producers set to stress the integral nature of the technology to reaching net zero. CCS-related announcements – such as this one – are likely to feature prominently.

CCS: Fact vs Fiction

Watch the video explainer

IEA and IPCC perspectives

Despite the Oil and Gas industry saying that CCS will play a crucial role in reducing emissions, the IEA and IPCC scenarios indicate at most a strictly limited role for CCS. Use must be confined to hard to abate industrial sectors, such as cement.

According to the IEA, with greater investment in already proven renewable energy technologies, it won’t be necessary to expand fossil fuel-based CCS to reach net zero by 2050.

“Continuing with business-as-usual for oil & gas while hoping a vast deployment of carbon capture will cut the emissions is fantasy,” IEA executive director Fatih Birol said late November.

The IPCC also cautions against overreliance on CCS and related technologies, noting their future deployment is uncertain, they face multiple feasibility constraints, and could have adverse impacts on human rights and ecosystems.

Watch Fatih Birol, Executive Director, IEA

The Oil and Gas Industry in Net Zero Transitions

The main limitations of CCS

Leakage and liability

The science around long term CO2 storage is very questionable, making leaks not just likely but inevitable. A leak could be explosive, putting lives at risk, or pollute the local environment – not to mention rendering any climate benefits null and void.

Beyond the physical danger, there is also the question of liability: private companies are unlikely to be able to assume risks and costs indefinitely – as we’ve already seen in Australia with Chevron – leaving governments to foot the bill for the clean up.

Let's hear from the experts

Outrageous price tag

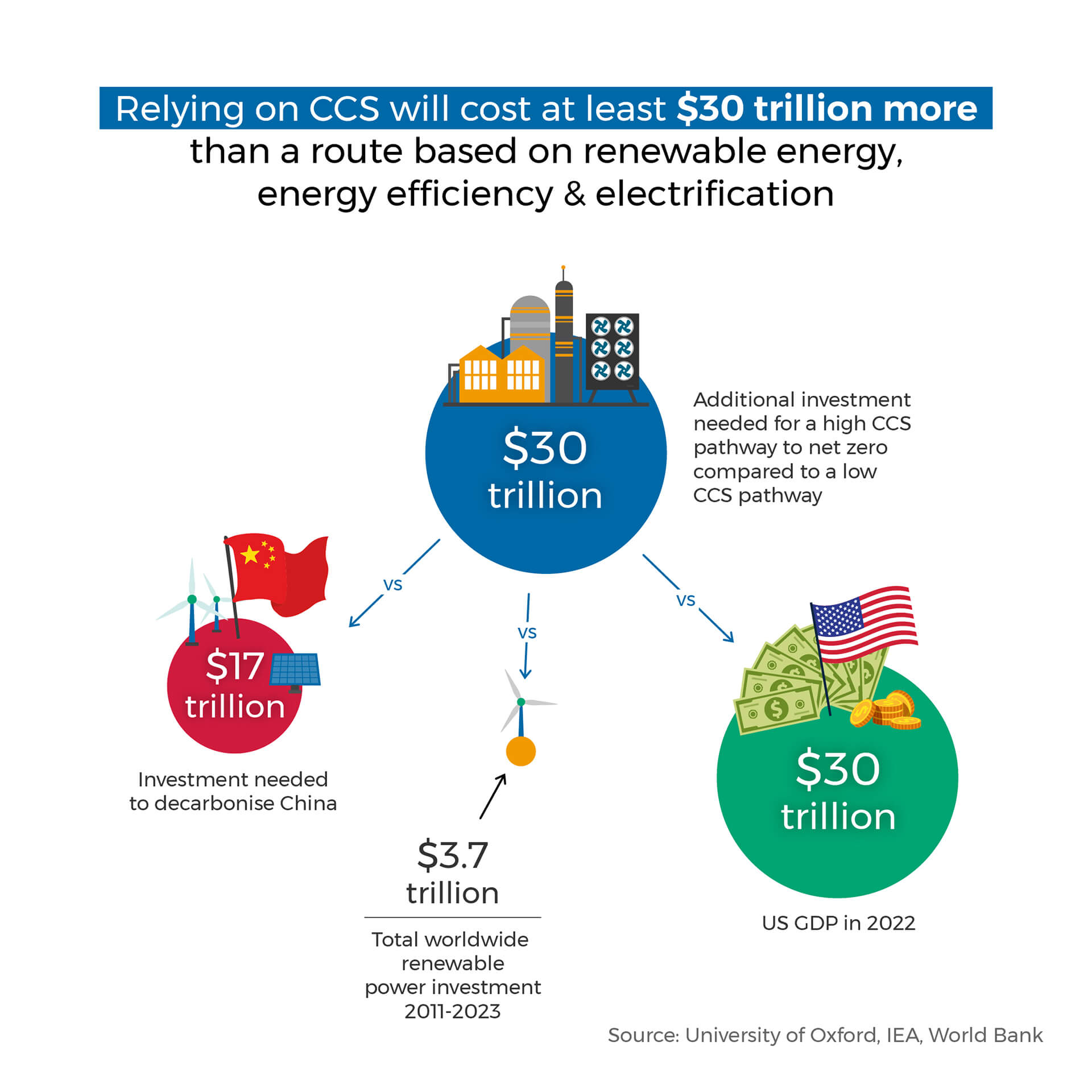

Relying on carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reach net zero would cost governments around the world at least $30 trillion more than a route based on renewable energy, energy efficiency and electrification, according to research from The University of Oxford.

That crazy figure is roughly twice what it would cost to decarbonise China. Even if the money was available, it’s far too risky an approach and simply delays our transition to a low carbon economy. We must focus instead on phasing out fossil fuels and investing more in proven, low cost renewable energy solutions.

Let's hear from the experts

What failure looks like

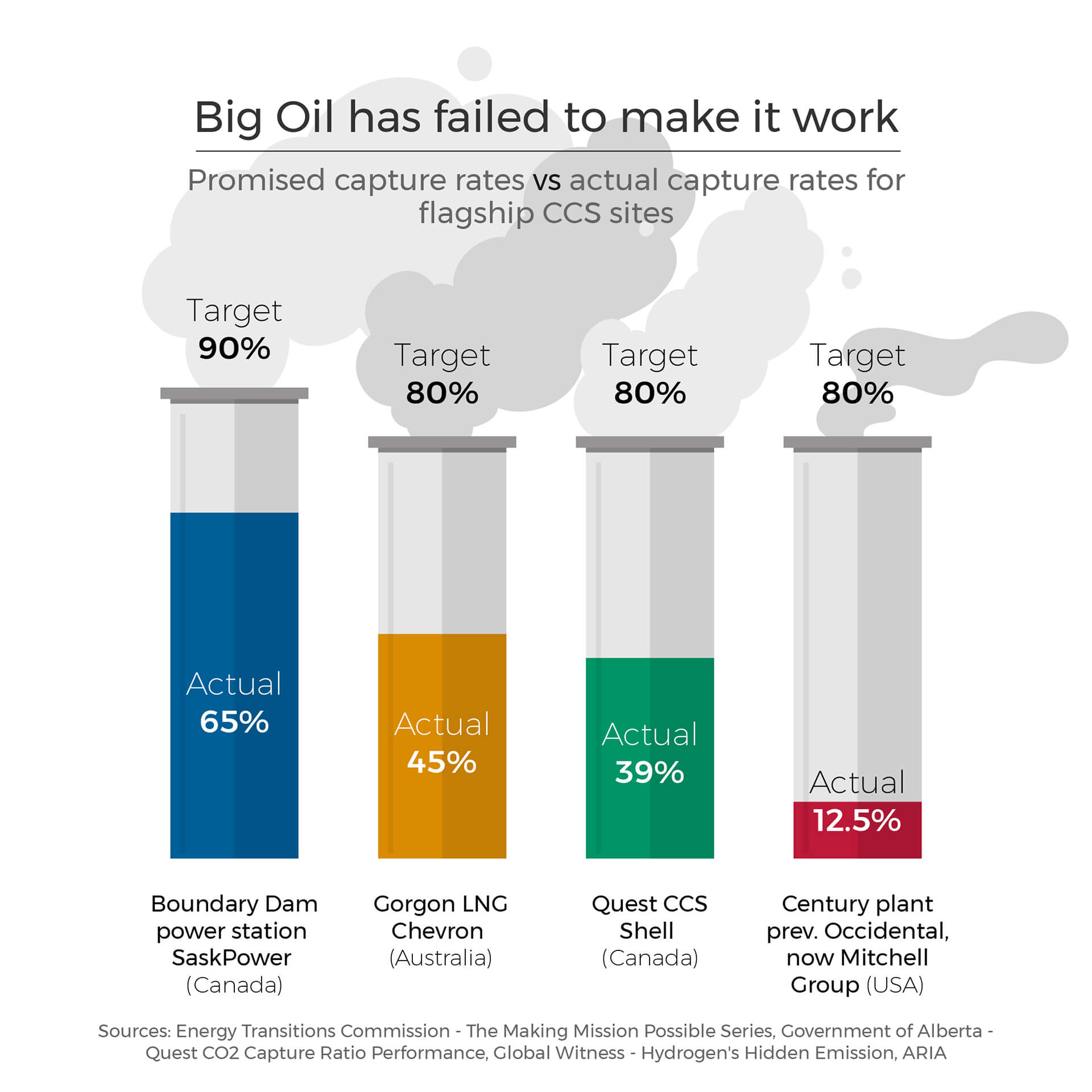

CCS was invented 50 years ago and is still nowhere near commercially viable. Even where oil companies have managed to install it, the technology simply doesn’t capture anything like as much CO2 as it’s meant to.

Chevron, for example, forecast capture rates in excess of 80% at its Gorgon LNG project in Australia but so far has failed to even reach 50%. And Gorgon has been one of the better performers; a recent investigation into the Century CCS plant in Texas found that capture rates were less than 12.5% of nameplate capacity before Occidental Petroleum quietly sold off the asset in January 2022.

The rate of CCS deployment has also been slowing. According to the IEA, less new CO2 capture capacity was added between 2015 and 2022 than between 2010 and 2015.

Let's hear from the experts

Unviable in the timeframe

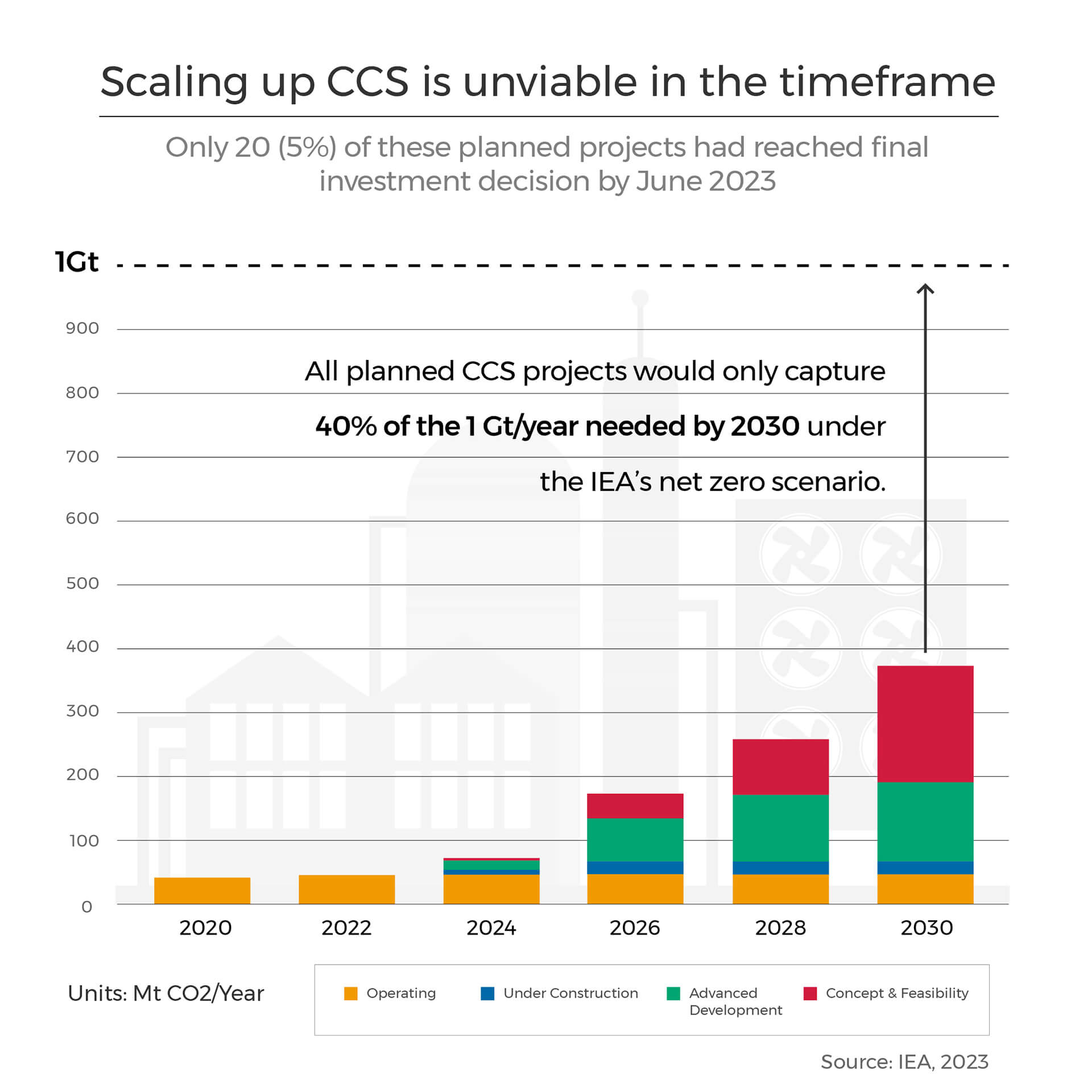

If every one of the CCS projects in the pipeline today were realised, CCS capacity would rise nearly tenfold. But a CCS build-out at that speed is utterly implausible, given only 5% of those projects in the pipeline have reached FID. And even if it could be done, it still wouldn’t even capture half the amount of CO2 the IEA says is needed by 2030.

It’s not cookie-cutter technology

CCS technology would be a lot more straightforward if all CO2 emitting facilities were designed the same. That’s not the case; it’s bespoke and site-specific, which means opportunities for learning-by-doing advances are thin on the ground and cost improvements are slow. So drawing parallels with the rapid fall in cost of RENs – like solar – is way wide of the mark.

Let's hear from the experts

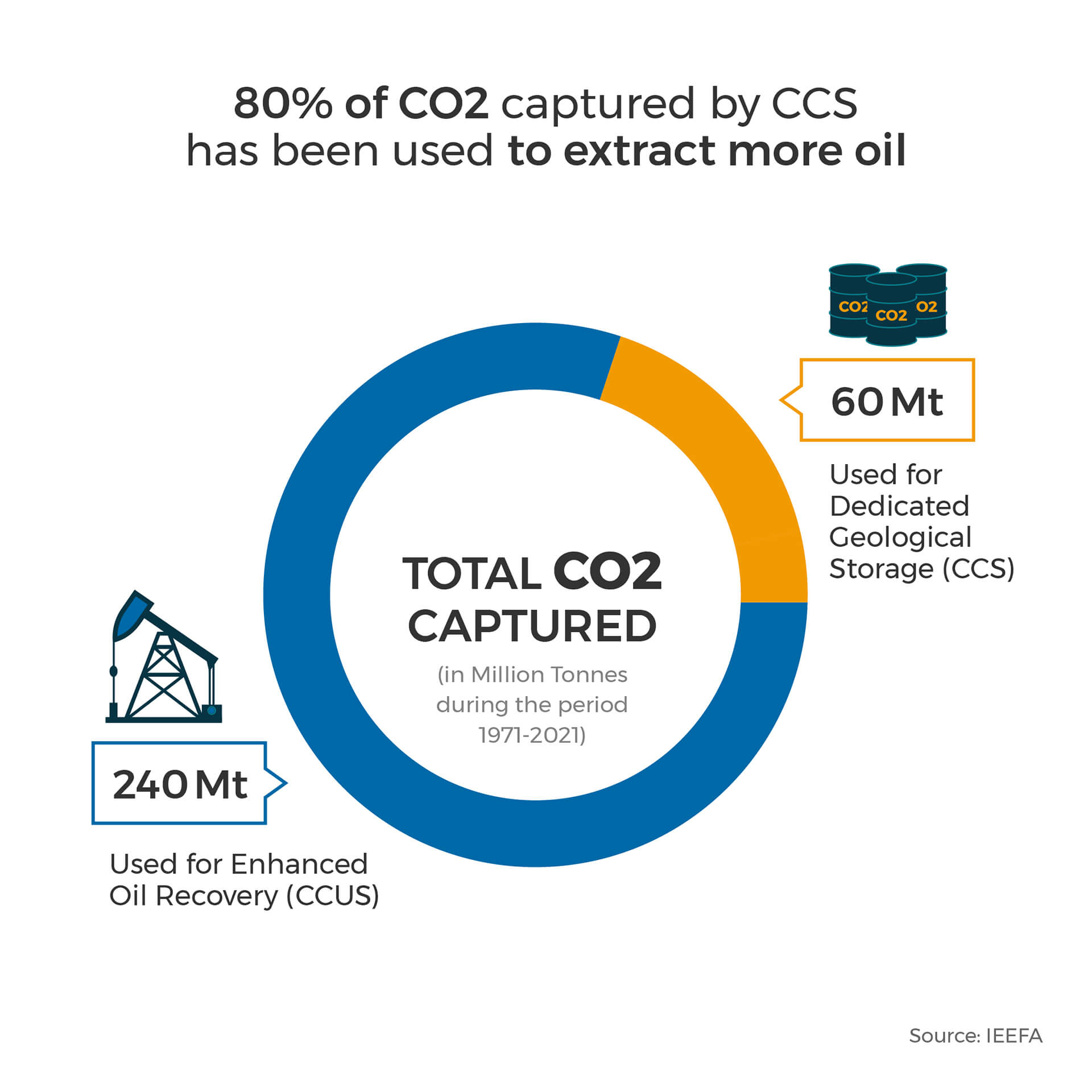

CO2 is not actually being stored

The CCS process is meant to end with CO2 being stored permanently underground, but that’s not what happens in practice. At present, nearly three quarters of CO2 captured annually is not stored, but reinjected into oil fields to push more oil and gas out of the ground in a process called Enhanced Oil Recovery.

Let's hear from the experts

Looks like a no-brainer

This is a choice between exceptionally expensive and unproven technologies that may or may not deliver in decades to come or a range of cheap, clean renewable technologies that are proven to deliver the emissions reductions we so desperately need.