Finance has been one of the main sticking points throughout COP26 and, as yet, no significant breakthroughs have been made. This is one of the key areas the conference will be judged on, and much of the increasingly fraught, last-minute negotiations will centre on cold hard cash. These are the key areas to watch out for…

- The USD 100 billion

Developed countries promised way back in 2009 to provide USD 100 billion a year to developing countries by 2020. They failed. Most estimates suggest they managed about USD 80 billion. Developing countries have made clear throughout COP that this shortfall is a significant blow for trust that has left them with a massive funding gap.

A week before the COP, Canada, Germany and the UK announced a delivery plan for the full amount, which they said “makes significant progress towards the $100 billion goal in 2022, and provides confidence that it will be met in 2023”. However, vulnerable countries say it’s imperative that developed countries deliver at least USD 500 billion over the period 2020-2024. The second draft of the final text finally acknowledges, “with deep regret”, that promises have not been met, but provides no more detail on when or how the money will be delivered, beyond “urging” developed countries to pay it “urgently”.

- Adaptation finance

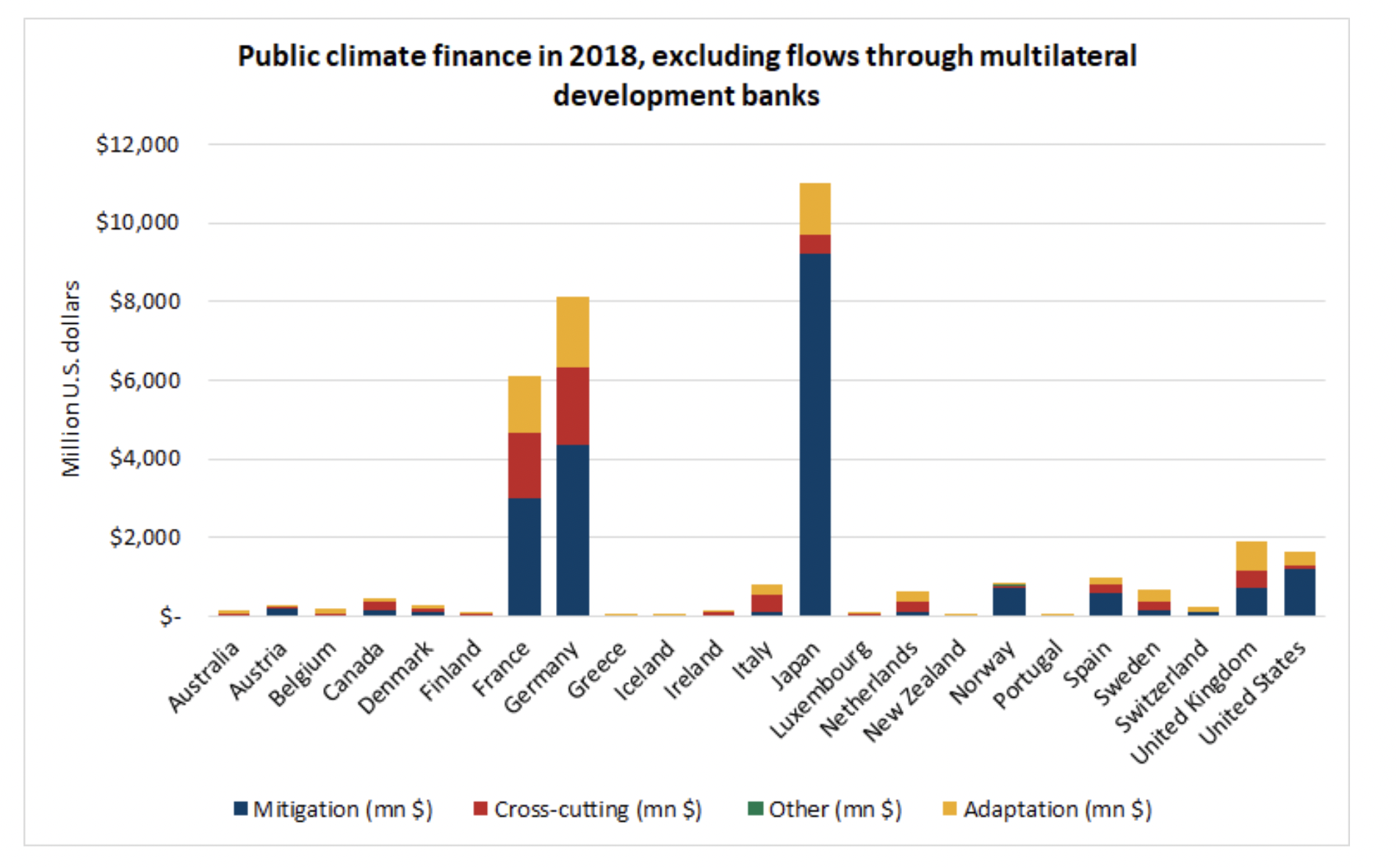

Only about a quarter of climate finance for developing countries goes towards adaptation. Developing countries have said this balance should be 50:50.

The goal, included in the current version of the final text, is for developed countries to collectively double their contributions to adaptation finance from 2019 levels as soon as possible, and by 2025 at the latest. However, behind the scenes, developed countries, including the US, are pushing for a commitment that individual countries double their adaptation finance.

But some of the largest largest contributor countries – Japan, France, Germany and the US included – provide only a fraction of their climate finance as adaptation. They need to do much more than double to reach 50:50. For example, the US has committed to increase its adaptation finance sixfold by 2024, but this will still only represent about a quarter of its overall climate finance.

- Loss & Damage

Two years after the Santiago Network on Loss & Damage, eight years on from the Warsaw International Mechanism, and 20 years after it was first raised, developing countries say this COP has to include concrete, near-term commitments on loss and damage (L&D) – including how to provide finance for countries hit by climate disasters (not just “technical assistance”).

So far, developed countries have dodged this demand, although Scotland last week announced GBP 2 million “seed funding” for L&D. The calls for L&D finance are becoming clearer, with many climate-vulnerable developing countries raising the topic in the negotiations.

L&D is separate to the finance agenda, but its finance component is important. The G77 has called for the establishment of an L&D finance facility – the “Glasgow Facility” – with a process to work out how to get it up and running at COP27. Additional progress in Glasgow could include a concrete, near-term commitment to assessing gaps in L&D funding.

- Different forms of finance

Loss and damage funds, and ideally most climate finance, need to be in the form of grants, for reasons of both economics and equity. L&D compensates people for a crisis they have just suffered (and, as low emitting countries, for which they are not responsible), quite probably impacting their economic growth. Providing L&D finance as debt would simply place an even greater burden on already weakened finances.

A new text shared on 12 November includes a direct reference to the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), that could provide climate finance to vulnerable countries. These are a special type of international currency that have, to date, been used by rich countries that need them least. To address this imbalance, the IMF has set up a new facility, called the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, or RST, through which wealthy countries could rechannel SDRs to low and climate-vulnerable countries. G20 finance ministers endorsed its creation last month, but the full details won’t be known until early next year.

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley has proposed that an annual SDR allocation of USD 500 billion could be used to channel much-needed transition finance to developing countries, but any deal would be outside the COP process.